01/24/2023 — After a decade of muted price gains, inflation fears have cropped up again as the costs of many goods and services have spiked this year. The ongoing pandemic has played a leading role in the jump in inflation as lingering COVID-induced supply chain disruptions have made it difficult to find some items while driving up consumer prices. Predicting future inflation can be difficult as current readings only reflect where prices have been trending rather than where they are headed. Moreover, temporary supply or demand shocks within specific industries (I.e. – oil and gasoline) can swing inflation for periods of time. For these reasons, tracking the longer-term influences on price gains can provide a clearer picture of the inflation outlook.

Historical impact of pandemics on the economy

Historically, health pandemics have caused significant shocks to the U.S. economy. Flu pandemics in 1957 and 1968 were followed by economic downturns while the 1918 Spanish flu was extremely disruptive to the entire society at the time. The nature of a pandemic causes both a demand shock as consumers pull back on activity and a supply shock as businesses shut down or reduce operations. Moreover, there is little to no warning for consumers, businesses, or governments that an extreme shock will occur, making for a sharp shift in overall economic conditions.

The supply shock component of the pandemic has the largest impact on inflation as the productive capacity of the economy falls. For example, the oil supply shocks of the 1970s helped to cause the highest spikes in consumer inflation seen over the past 70 years. As the economy comes out of the pandemic, demand will increase, potentially sharply, surpassing the ability of businesses to supply products. This could lead to shortages of goods and services and higher prices for the items that are available.

Short term impact of the pandemic on inflation

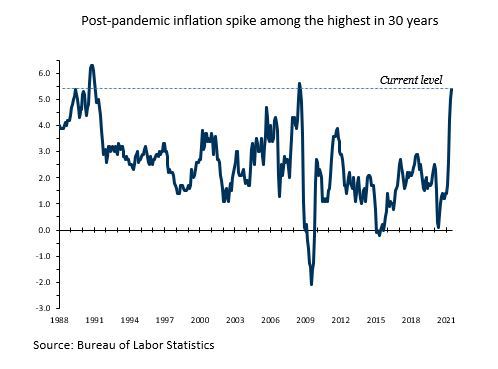

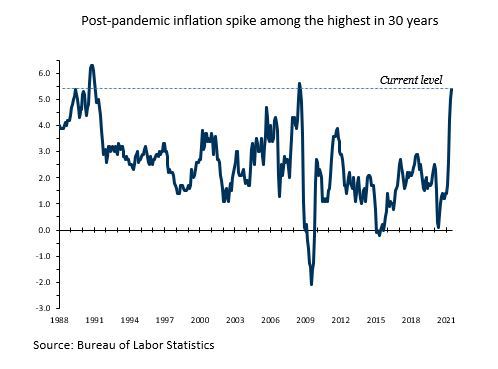

Inflation typically increases coming out of downturns as demand outpaces supply early in the recovery, but this tendency has been exacerbated by COVID-19 impacts. Demand for many goods dropped in 2020 and remained lower into 2021 as further waves of COVID cases led to government restrictions on consumer behavior. As cases waned in the spring of 2021, these restrictions were mostly lifted, driving a surge in demand. Supply conditions of many inputs (I.e. – lumber, steel, and microchips) were depressed during the pandemic, too — in anticipation of reduced demand with the downturn and due to pandemic limits on the number of workers. Once the economy reopened more fully, total production within many industries lagged as businesses had difficulty finding inputs and workers. The resulting supply crunch led to higher costs for producers which were passed into many of the prices seen on shelves, with the annual change in the consumer price index spiking to 5.4 percent in mid-2021.

While the pandemic remains disruptive for many parts of the global supply chain, including shipping and ground transportation, these impacts should fade in the second half of 2021 and into 2022. As such, the Federal Reserve and many economists feel that the recent rise is an example of transitory inflation.

What is transitory inflation?

This is a period where prices spike temporarily due to an imbalance between supply and demand in the market, as has occurred over the past year. Once the shock passes and supply chains heal, inflation should settle at a lower level that is more in line with long-term trends. Most forecasts project that inflation will fall to around 2.5 percent by the end of 2022.

Long term post-pandemic outlook on inflation

Not all the recent price increases are expected to be transitory, however, as lingering pandemic impacts could drive up wages and housing costs for several more years. Average inflation over the next five years could be slightly higher than the pre-COVID trend as a result, running between 2.5-3.0 percent. Still, it is expected that inflation expectations will remain in check as longer-term price depressants caused by increased online purchases (the so-called “Amazon effect”) and the offshoring of production should continue. Moreover, one of the objectives of the Federal Reserve is long-run price stability which they define as an average of 2.0 percent annual inflation. While the Fed will likely let inflation run above its 2.0 percent target for a short period of time, economic conditions should improve enough to prompt interest rate increases by late 2023. The eventual tightening of monetary policy will act to slow the economy and, thus, prices — keeping inflation near its long-run average.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been highly disruptive for the U.S. economy with effects that could linger for years. While price gains have increased sharply this year, much of the recent inflationary pressure is expected to be transitory as COVID impacts on supply chains fade heading into 2022. There is a risk that inflation could run hotter than expected in the future, but long-term price depressants and eventual Fed action should keep inflation in check beyond the current spike. Still, given the uncertainty around forecasting inflation, these trends bear watching for an unexpected shift in prices.